British Rail

|

|

| Industry | Land and sea transport |

|---|---|

| Fate | Privatised |

| Successor | National Rail |

| Founded | 1948-1962 part of the BTC 1962-present British Railways Board |

| Defunct | 2000 |

| Headquarters | Great Britain and adjacent waters |

| Parent | British Transport Commission (until 1962), British Railways Board (since 1962) |

British Railways (BR), which from the 1960s traded as British Rail, was the operator of most of the rail transport in Great Britain between 1948 and 1997. It was formed as a result of the nationalisation of the "Big Four" British railway companies and lasted until the gradual privatisation of British Rail in stages between 1994 and 1997. Originally a trading brand of the Railway Executive of the British Transport Commission, it became an independent statutory corporation in 1962: the British Railways Board.

The period of nationalisation saw sweeping changes in the national railway network; a process of dieselisation occurred which saw steam traction eliminated in 1968, in favour of diesel and electric power. Passengers replaced freight as the main source of business and one third of the network was closed by the Beeching Axe of the 1960s.

The British Rail "double arrow" logo is formed of two interlocked arrows showing the direction of travel on a double track railway and was nicknamed "the arrow of indecision".[1] It is now employed as a generic symbol on street signs in Great Britain denoting railway stations, and as part of the Association of Train Operating Companies' jointly-managed National Rail brand—being still printed on railway tickets.[2]

Contents |

History

Nationalisation in 1947

The rail transport system in Great Britain developed during the 19th century. After the grouping of 1923 under the Railways Act 1921 there were four large railway companies, each dominating its own geographic area: the Great Western Railway (GWR), the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) and the Southern Railway (SR). During World War I the railways were under state control, which continued until 1921. Complete nationalisation had been considered, and the Railways Act 1921 [3]is sometimes considered as a precursor to that, but the concept was rejected; nationalisation was subsequently carried out after World War II, under the Transport Act 1947. The Transport Act 1947 made provision for the nationalisation of the network, as part of a policy of nationalising public services by Clement Attlee's Labour Government. British Railways came into existence as the business name of the Railway Executive of the British Transport Commission (BTC) on 1 January 1948 when it took over the assets of the Big Four.[4]

There were also joint railways between the big four and a few light railways to consider - see list of constituents of British Railways. Excluded from nationalisation were industrial lines like the Oxfordshire Ironstone Railway; narrow-gauge railways, like the Ffestiniog Railway were also excluded, apart from two which were already owned by a company which was itself to be nationalised. The London Underground, which had been publicly owned since 1933, was also nationalised, becoming the London Transport Executive of the British Transport Commission. The Bicester Military Railway was already run by the government.

The Railway Executive was conscious that some lines on the (then very dense) network were not profitable and also hard to justify socially, and a modest programme of closures was begun. However, the general financial position of BR became gradually worse, until an operating loss was recorded in 1955. The Executive itself had been abolished in 1953 by the incoming Conservative government, and control of BR transferred directly to the parent Commission. Other changes to the British Transport Commission at the same time included the return of road haulage to the private sector.

1955 Modernisation Plan

Also in 1955, a major modernisation programme costing £1.2 billion was authorised by the government. This included the withdrawal of steam traction and its replacement by diesel (and some electric) locomotives. Not all the modernizations would be effective at reducing costs: many classes of sometimes experimental locomotives were bought, and a number of marshalling yards were built at a time when wagon load freight was already being replaced by train load workings, which do not need complex shunting and reforming.

The report latterly known as the "Modernisation Plan"[5] was published in December 1954. It was intended to bring the railway system into the 20th century. A government White Paper produced in 1956 stated that modernisation would help eliminate BR's financial deficit by 1962. The aim was to increase speed, reliability, safety and line capacity, through a series of measures which would make services more attractive to passengers and freight operators, thus recovering traffic that was being lost to the roads. The important areas were:

- Electrification of principal main lines, in the Eastern Region, Kent, Birmingham and Central Scotland;

- Large-scale dieselisation to replace steam locomotives;

- New passenger and freight rolling stock;

- Resignalling and track renewal;

- Closure of small number of lines which were seen as unnecessary in a nationalised network, as they duplicated other lines.

The Beeching report

During the late 1950s, railway finances continued to worsen, and in 1959 the government stepped in, limiting the amount the BTC could spend without ministerial authority. A White Paper proposing reorganisation was published in the following year, and a new structure was brought into effect by the Transport Act 1962.[6] This abolished the Commission and replaced it by a number of separate Boards. These included a British Railways Board, which took over on 1 January 1963.

Following semi-secret discussions on railway finances by the government-appointed Stedeford Committee in 1961, one of its members, Doctor Richard Beeching, was offered the post of chairing the BTC while it lasted, and then becoming the first Chairman of the British Railways Board.[7]

A major traffic census in April 1961, which lasted one week, was used in the compilation of a report on the future of the network. This report - The Reshaping of British Railways - was published by the BRB in March 1963 ("the Beeching Axe").[8][9] Its proposals were dramatic. A third of all passenger services and more than 4000 of the 7000 stations would close. Beeching, who is believed to have been the author of most of the report, set out some dire figures. One third of the network was carrying just 1% of the traffic. Of the 18,000 passenger coaches, 6,000 were said to be used only 18 times a year or less. Although maintaining them cost between £3m and £4m a year, they earned only about £0.5m.[10]

Most of the closures were carried out between 1963 and 1970 (including a few that were not listed in the report). Some closures originally listed were not carried out. The closures transformed the railway. Freight in particular underwent a revolution as the Victorian network of thousands of small yards was progressively abolished in favour of comparatively few major terminals.

The closures were heavily criticized at the time,[11] and continue to attract criticism today.[12] Since privatization, efforts have been made to re-open some of the lines closed under the Beeching program.[13]

A second Beeching report, The Development of the Major Trunk Routes, followed in 1965. This did not recommend closures as such, but outlined a "network for development". The fate of the rest of the network was not discussed in the report.

Post-Beeching

The basis for calculating passenger fares changed in 1964. In future, fares on some routes - such as rural, holiday and commuter services - would be set at a higher level than on other routes; previously, fares had been calculated using a simple rate for the distance travelled, which at the time was 3d per mile second class, and 4 1⁄2d per mile first class[14] (equivalent to £0.19 and £0.28 respectively, as of 2011[15]).

Passenger levels decreased steadily from the late 1950s to late 1970s,[16] but experienced a renaissance with the introduction of the high-speed Intercity 125 trains in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[17]

The 1980s saw pressure to reduce government funding and above-inflation increases in fares. A further British Rail report, from a committee chaired by Sir David Serpell, was published in 1983. The Serpell Report made no recommendations as such, but did set out various options for the network including, at their most extreme, a skeletal system of less than 2000 route km. This report was not welcomed, and even the government decided to quietly leave it on the shelf. Meanwhile, BR was gradually re-organised, with the regional structure finally being abolished and replaced with business-led sectors. This led to far greater customer focus, but was cut short in 1994 with the splitting up of BR for privatisation.

Upon sectorisation in 1982, the passenger sectors created were InterCity (principal express services) and Network SouthEast (mainly London commuter services).[18] Provincial was responsible for all other passenger services, except in the metropolitan counties, where local services were managed by the Passenger Transport Executives. Regional Railways was one of the three passenger sectors of British Rail created in 1982 that existed until 1996, two years after privatisation. The sector was originally called Provincial. Regional Railways was the most subsidised (per passenger km) of the three sectors. Upon formation, its costs were four times its revenue.[18]

The Clapham Junction rail crash occurred on the morning of 12 December 1988. Two collisions involving three trains occurred slightly south-west of the station. Thirty-five people died and more than 100 were injured. The immediate cause of the crash was incorrect wiring work in which an old wire, incorrectly left in place after rewiring work and still connected at the supply end, created a false feed to a signal relay, thereby causing its signal to show green when it should have shown red.[19]

The privatisation of British Rail

Between 1994 and 1997, British Rail was privatised.[20] Ownership of the track and infrastructure passed to Railtrack on 1 April 1994; afterwards passenger operations were franchised to individual private-sector operators (originally there were 25 franchises); and the freight services sold outright (six companies were set up, but five of these were sold to the same buyer).[21] The remaining obligations of British Rail were transferred to BRB (Residuary) Ltd.

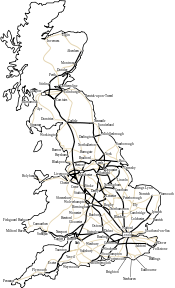

Network

The former BR network, with the trunk routes of the West Coast Main Line, East Coast Main Line, Great Western Main Line and Midland Main Line, remains mostly unchanged since privatisation. Several lines have reopened and more are proposed, particularly in Scotland and Wales where the control of railway passenger services is devolved from central government. However, in England passenger trains have returned to Corby, Chandlers Ford reopened line to Aylesbury Vale Parkway and there are numerous other proposals to restore services, such as Oxford-Milton Keynes/Aylesbury, Lewes-Uckfield and Plymouth-Tavistock.

In Wales, the Welsh Assembly Government successfully supported the re-opening to passenger services, of the Vale of Glamorgan Line between Barry and Bridgend in 2005. In 2008 the Ebbw Valley Railway reopened between Ebbw Vale Parkway and Cardiff, with services to Newport scheduled to commence by 2011. (The Barry-Bridgend route was included in the closures proposed in the Beeching report of March 1963 and its services were duly withdrawn in June 1964, but Ebbw Vale had already been closed to passengers before the report was published.)

In Scotland the Scottish Executive/Government have reinstated the lines between Hamilton and Larkhall, Alloa and Stirling and work is underway to link Airdrie to Bathgate. The biggest line reinstatment project is the former Waverley railway Edinburgh to Borders line.[22]

Successor companies

Under the process of British Rail's privatisation, operations were split into more than 100 companies. The ownership and operation of the infrastructure of the railway system was taken over by Railtrack.

The Telecomms infrastructure and British Rail Telecommunications was sold to Racal which in turn sold onto Global Crossing and merged with Thales Group.

The rolling stock was transferred to three private ROSCOs (ROlling Stock COmpanies). Passenger services were divided into 25 operating companies, which were let on a franchise basis for a set number of years, whilst freight services were sold off completely. Dozens of smaller engineering and maintenance companies were also created and sold off.

British Rail's passenger services came to an end upon the franchising of ScotRail; the final train that the company operated was a Railfreight Distribution freight train in Autumn 1997. The British Railways Board continued in existence as a corporation until early 2001, when it was replaced with the Strategic Rail Authority.

Since privatisation, the structure of the rail industry and number of companies has changed a number of times as franchises have been relet and the areas covered by franchises restructured. Franchise-based companies that took over passenger rail services include:

- Midland Mainline – superseded in 2007 by East Midlands Trains

- Great North Eastern Railway – superseded in 2007 by National Express East Coast which has since been brought back full circle into public ownership with the creation of the new government controlled East Coast operator.

- Virgin Trains (West Coast)

- Virgin CrossCountry – superseded in 2007 by CrossCountry

- ScotRail operated by National Express - superseded in 2004 by First ScotRail (now branded as ScotRail - Scotland's Railway)

- Great Western Trains – from 1998: First Great Western

- Wales and West – became Wessex Trains and Wales and Borders (including the Cardiff Railway Company services operated as Valley Lines) in 2001, after being split into two separate franchises, and now run by First Great Western and Arriva Trains Wales

- Arriva Trains Northern (originally Northern Spirit) – superseded in 2004 by First TransPennine Express and Northern Rail

- First North Western (originally North Western Trains) – superseded in 2004 by First TransPennine Express and Northern Rail

- Anglia Railways, Great Eastern, (later First Great Eastern and the West Anglia section of WAGN were all merged to become ONE later renamed National Express East Anglia

- Thameslink and Great Northern Section of WAGN grouped together to form First Capital Connect as part of the Thameslink Great Northern Franchise

- LTS later renamed c2c

- Connex South Eastern became South Eastern Trains, then Southeastern

- Connex South Central became South Central and later renamed Southern

- Merseyrail Electrics for a period called Arriva Trains Merseyside

- South West Trains

- Central Trains – divided in 2007 between London Midland, Cross Country and East Midlands Trains

- London Underground for the short underground Waterloo & City line

Gallery

Diesel Class 47 loco No.47100 with the trademark Stratford T.M.D. silver roof |

Class 87 electric locomotive and Mark 3 coaches franchised by Virgin Trains |

A Class 156 DMU at Coventry in 2000. It is still in the old BR livery, but has a Central Trains name tag. |

See also

- History of rail transport in Great Britain

- British Rail brand names

- British Rail corporate liveries

- British Rail flying saucer

- British Rail sandwich

- British Carriage and Wagon Numbering and Classification

- British Rail locomotive and multiple unit numbering and classification

- British Transport Police

- Gerry Fiennes

- List of British Rail classes

- List of companies operating trains in the United Kingdom

- London Underground

- Glasgow Subway

- Tyne and Wear Metro

- Liverpool Overhead Railway

- Steam locomotives of British Railways

- Sealink BR's sea division

- National Preservation

- National Rail

- Network Rail

- Rail transport in Great Britain

- Privatisation of British Rail

References

- ↑ Shannon, Paul. "Blue Diesel Days". Ian Allan Publishing. http://www.ianallanpublishing.com/product.php?productid=56658&cat=1027&bestseller=Y. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Her Majesty's Government (2002). "The Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions 2002 (SI 2002:3113)". http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2002/023113dh.gif. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates, House of Lords, 1920-08-03 , columns 711–713

- ↑ Her Majesty's Government (1947). "Transport Act 1947". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=67. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ British Transport Commission (1954). "Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Rail". The Railways Archive. (Originally published by the British Transport Commission). http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=23. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ Her Majesty's Government (1962). "Transport Act 1962". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=116. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ "Back to Beeching", BBC Radio 4, Thursday 27 February 2010

- ↑ British Transport Commission (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 1: Report". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=13. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ British Transport Commission (1963). "The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 2: Maps". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=35. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- ↑ Page 15, "The Reshaping of British Railways", Dr Richard Beeching

- ↑ "The Economics and Social Aspects of the Beeching Plan" - Lord Stoneham, House of Lords, 1963]

- ↑ "Can Beeching be undone?". 2009. http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/2009/06/can-beeching-be-undone.html.

- ↑ "Move to reinstate lost rail lines", BBC, 15 June 2009

- ↑ Cooke, B.W.C., ed (July 1964). "Notes and News: New fares structure". Railway Magazine (Westminster: Tothill Press) 110 (759): 592.

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Measuring Worth: UK CPI.

- ↑ The UK Department for Transport (DfT), specifically Table 6.1 from Transport Statistics Great Britain 2006 (4MB PDF file)

- ↑ Marsden, Colin J. (1983). British Rail 1983 Motive Power: Combined Volume. London: Ian Allen. ISBN 0-7110-1284-9.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Thomas, David St John; Whitehouse, Patrick (1990). BR in the Eighties. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-9854-7.

- ↑ Hidden Inquiry Report (PDF), from The Railways Archive

- ↑ Her Majesty's Government (1903). "Railways Act 1993". The Railways Archive. (originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office). http://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docSummary.php?docID=12. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "EWS Railway - Company History". http://www.ews-railway.co.uk/about/history.html. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "Waverley Rail Project route". http://www.waverleyrailwayproject.co.uk/route.php.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||